// Place Provocations: Is graffiti good?

- benstephenson

- Oct 6, 2025

- 5 min read

With graffiti artist Banksy's latest work skewering the judiciary on the walls of the Rayal Courts of Justice, BEN STEPHENSON takes a look at the relationship between place and graffiti, asking: can graffiti be good for cities?

My first real job in London was managing a cleaning contract on the rapidly regenerating South Bank.

This was in the time before Banksy was a 'thing', but a big part of that job was to direct the removal of work by Banksy and other graffiti artists from the sides of buildings.

We removed countless Banksy rats. We removed a dribble of paint that stretched in a wobbly white line the entire length of the embankment, ending with a policeman on his knees with a straw, as though he was snorting a line of cocaine. We removed work from the porous Portland stone of Waterloo Bridge and the reinforced concrete of the National Theatre.

I thought at the time that Banksy's work was witty and interesting, but justified its removal to myself on aesthetic and professional grounds. It wasn’t up to me to make decisions on what graffiti merited saving on artistic grounds - the job was to remove all the graffiti, end of discussion.

I concluded that Banksy's battle with The Man was as much a part of the art as the artwork itself - that the nature of the medium meant that the works were designed to be temporary. Want your art to last forever? Don’t spray it on the outside wall of a building, someone's just going to come along and remove it.

A couple of years later in 2008, Banksy arrived into popular consciousness, curating the brilliant Cans Festival close by in Leake Street, Waterloo. That bank holiday event saw queues of people forming up to see his and other graffiti artists' work, transforming the space permanently into an ever-changing art exhibition. Today, the Leake Street graffiti tunnel continues to attract crowds to admire the art and lend some urban cache to their Instagram reels.

This was about the time the country started to have a more nuanced reaction to graffiti and I began to question what we were doing too. Were we to be locked in an unwinnable and costly battle with graffiti artists in an attempt to keep the South Bank perpetually pristine? Was there another way to make sense of this thing?

We asked Central St Martin's Design Against Crime Research Centre to help us understand what we were doing, and began working with the wonderfully curious, sadly no longer with us, Marcus Willcocks. The research question was understanding the role graffiti has to play in the city, and our role as place managers in attempting to control it, which I was doing a pretty bad job at.

The questions kept coming. Does graffiti have a cultural significance that reflects values of inclusivity or is it a signifier of social decline? Can it be both at once? Does its meaning depend on the context or the merit of the work? What are the right principles by which to manage ostensibly progressive, privately-owned public spaces like the South Bank?

Though these questions were never truly answered, they were part of a fascinating debate in the years that followed, through the setting up of CSMs Graffiti Dialogues Network, and later as part of the planning battle for the South Bank Centre's Festival Wing undercroft, summarily won by the skaters and graffiti writers who still use the space today. Since that time we've experienced a shift in social attitudes around graffiti that has led to a relaxation in control.

I first experienced what places with uncontrolled graffiti felt like on a visit to Berlin. There you'll find it basically everywhere except on its memorials and museums, where clearly even Berlin finds it too much. Graffiti in Berlin is emblematic of the place's identity as a progressive, artistic city.

It had a more purposeful origin however. Before unification, graffiti was an important tool of political resistance, with the Berlin wall a giant canvas. The remaining bits of wall scattered around the city are now preserved as totems of that dissent, but look incongruously jolly, like giant slabs of birthday cake.

Graffiti-rich areas like Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain have come to be seen as global creative hubs, driving international visitors and spend to Berlin, contributing significantly to economic regeneration.

Similar things can be said of Le Panier, Marseille, Wynwood in Miami, and Coburg, Melbourne, where graffiti presents the backdrop to hipster photoshoots, gritty films and even weddings. In these places, graffiti attracts spend, visitors and reputation.

Coburg, Melbourne

In such places, the presence of graffiti for some seems to suggest a relaxation of surveillance, a laissez faire approach to public realm management. A sense that anything goes, and interesting, subversive things might happen.

Graffiti is a tool of irreverence, as exemplified in Banksy's recent piece on the Royal Courts of Justice. For many, it is a reflection of a self-aware, progressive society that tolerates free thinking and free speech. Walls in such societies become sites of dialogue, places to communicate pain, satire and anger. Tags might not be artistic, but vandalism, however intolerable, is an expression of disaffection we should probably listen to as a society.

Upfest, Bristol

For others though, graffiti heralds overtones of artwashing. In Bristol, Upfest, Europe's largest graffiti festival, is sometimes cited as an unwitting agent of gentrification, where graffiti might have once been seen as the signifier of degradation.

The same goes for Berlin, where regeneration has ended up pricing out those artists that once painted its walls. In these increasingly expensive painted cities, graffiti seems to stand less for artistic freedom and subversion as it does for the explosion of Air BnB.

Graffiti as a medium for communication is constantly changing. The South Bank wall previously featuring the cocaine snorting bobby is now the National Covid Memorial Wall, which is covered in tens of thousands of small red hearts. Here, graffiti is an act of remembrance and, given the location of the wall opposite parliament, of political warning.

The painting of St George's crosses across England's mini-roundabouts carries a similar air of warning and, like Banksy's work - although he may not delight in the comparison - makes a symbolic contribution to public discourse.

In all of these cases however, graffiti is a claim on space. Whether tags, satirical statements or sanctioned murals they all have the same role as a territorial marker. They are also exclusive, eliciting different effects on the viewer, forming in-groups and out-groups. You either get it or you don't. For the most part, its intent is to divide.

We've had graffiti since the Romans, it's going nowhere. So it looks as though we'll need to think harder about how we respond to it, particularly as place managers.

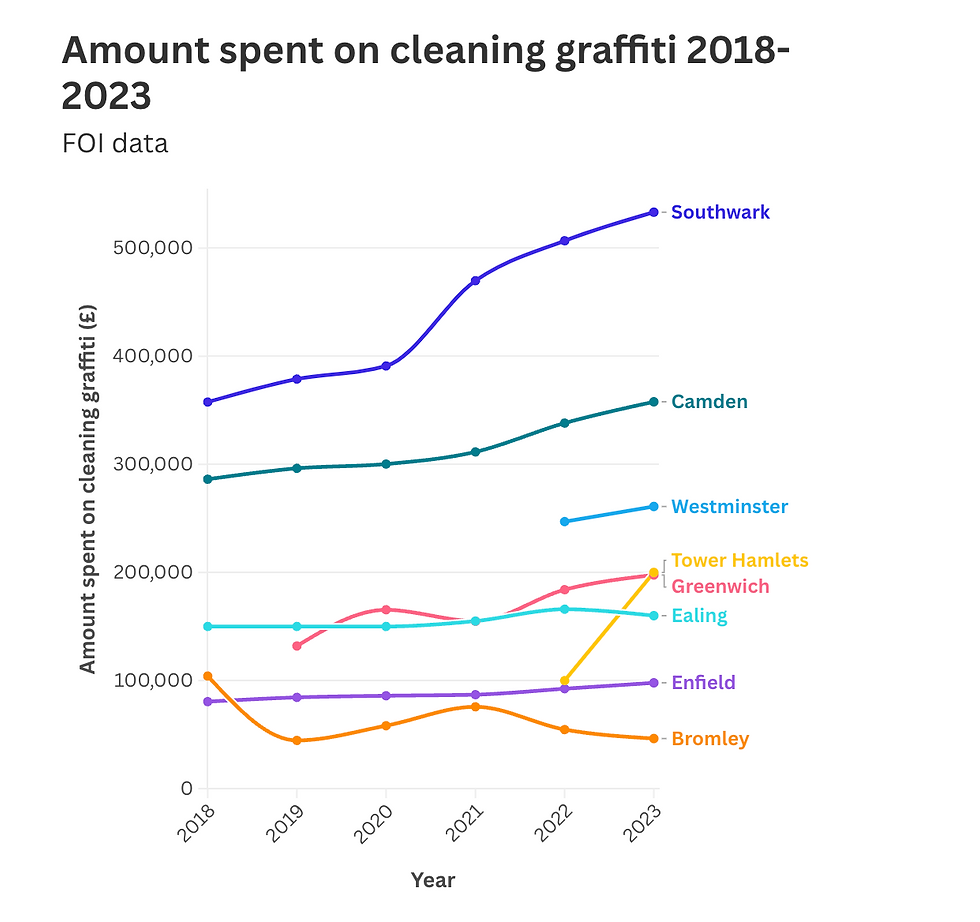

It's getting harder to do that. The cost of managing graffiti is increasing in many places in London, as the graph below shows, and reports of graffiti increased by 15% between 2022 and 2023, according to this article in South West Londoner.

Source: South West Londoner

So what should be our response to this rising burden?

For me, our role is to deliver spaces that are as inclusive as possible, and that means making them feel looked after.

Graffiti always has something to say, but it's significance as a contributor to placemaking in the long term is debatable. Most graffiti doesn't have the effect of improving public space or the perception of space.

And while it works in some - usually controlled - areas to attract artists, cultural production, and place vitality, on the whole it remains defined by its subversiveness and temporariness. It's destiny as an artwork is either to be painted over by another graffiti artist or obliterated by a jetwashing contractor.

So as a place manager, I continue to remove it, even if I can recognise in its vandalism a temporary, ephemeral, occasionally beautiful message.

Ben Stephenson is a placemaking consultant, and runs BAS Consultancy, helping create towns and cities that people like to be in. Email him on ben@basconsultancyhome.co.uk

Intuitive workflows simplify decision making, guiding users from best pen grips for arthritis preparation through serving, minimizing errors.

Supportive engagement assists clinical teams during challenging situations providing backup guidance and security guard companies santa barbara control so caregivers focus on treatment without distraction or fear when emotions run high tensions escalate.

Disclosure practices involve sharing relevant information promptly, helping stakeholders make informed choices while financial advisor for inheritance tax discouraging secrecy that could hide misconduct or poor performance.

Rural settings present different challenges distances weather exposure limited suppliers and lean to roof access requiring advance planning storage solutions and scheduling buffers while leveraging community knowledge.